Making Acute Care More Patient Centered – Patient Safety Learning Laboratory (PSLL)

Background

Diagnostic error in hospitalized patients is frequent, posing a threat to patient safety. Identifying at-risk patients, performing a risk assessment, and devising strategies to mitigate threats to patient safety may reduce the likelihood of harm.

Study Goals

To reduce patient harm, our AHRQ-funded Patient Safety Learning Laboratory (PSLL) utilized systems engineering (SE) and human factors (HF) methods to design, develop, and implement a suite of digital health tools integrated with our institution’s electronic health record (EHR) to proactively address threats to patient safety in real-time.

Our Approach

Our PSLL was comprised of two core teams and individual project teams to implement three project tools in the EHR.

The Administrative Core provided leadership and coordination for PSLL activities. They focused on communication, strategy selection for using Health Information Technology (HIT) to reduce hospital harm, and adherence to study design, timelines, and budgets.

The Systems Engineering, Usability, and Integration (SEUI) Core engaged with various hospital stakeholders and applied SE and HF methods to analyze problems and iteratively refine the digital health tools individually and as a combined toolkit.

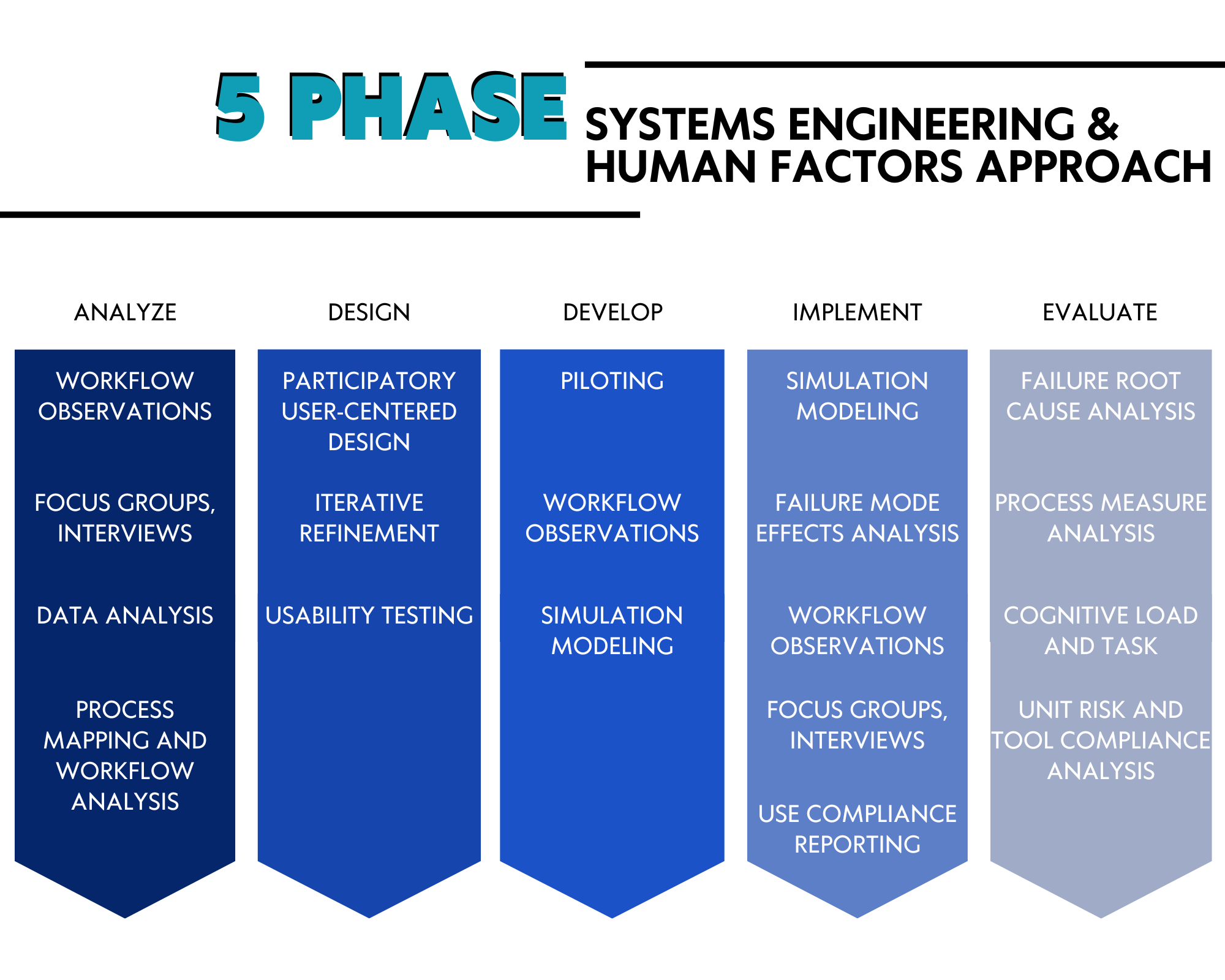

SE and HF methods were used during each phase of AHRQ’s 5-phase systems engineering project lifecycle: problem analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation.

Results

Three individual project tools were created. Read about each tool below

Fall TIPS

Fall TIPS is an electronic tool for clinicians and patients to engage in fall prevention by leveraging health information technology in the three-step fall prevention process.

Background

Falls are the most common cause of injury in older adults and being hospitalized puts adults at further risk for falls.

Unfamiliar surroundings, medications and treatments given in the hospital setting, and a decrease in activity level can cause patients to become mentally confused, weak, and unsteady. Even patients who were active and independent at home may require assistance to safely complete simple activities while they are in the hospital, such as such as getting out of bed or using the bathroom.

Project Goals

This project aims to help patients and family members work with nurses and other health care providers to reduce falls in the hospital by leveraging health information technology in the three-step fall prevention process.

Methods

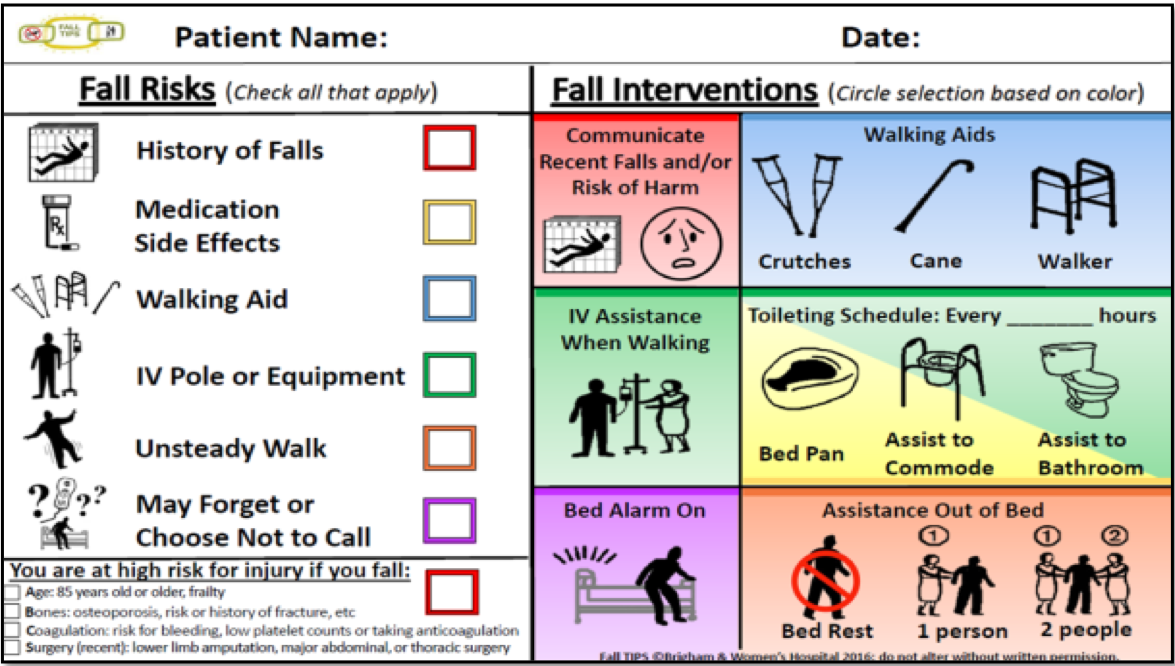

Using an iterative method, we developed both electronic and paper versions of the Fall TIPS tool to provide a fall risk assessment and individualized, evidence-based fall risk interventions.

Results

Patients receive an electronic tablet at the bedside to ensure secure access to their real-time safety plan.

The tablet displays patients’ fall risk factors and tailored fall prevention interventions, as well as educational content. For patients who choose not to use the electronic device, we developed a paper tool which communicates the personalized fall prevention plan to all members of the care team, including patients and families.

Patient Safety Dashboard

The Patient Safety Dashboard is a provider-facing dashboard assisting in the identification and reduction of patient safety threats before they manifest in actual harm.

Background

Inpatient adverse events (AEs) are injuries from medical management that can prolong hospital stays, cause harm and disabilities, or both. Health information technology (HIT) and electronic health records (EHRs) are being used to reduce these events.

However, current EHR systems can overwhelm clinicians with too much information and silo data. This harms interdisciplinary communication and patient safety.

Project Goals

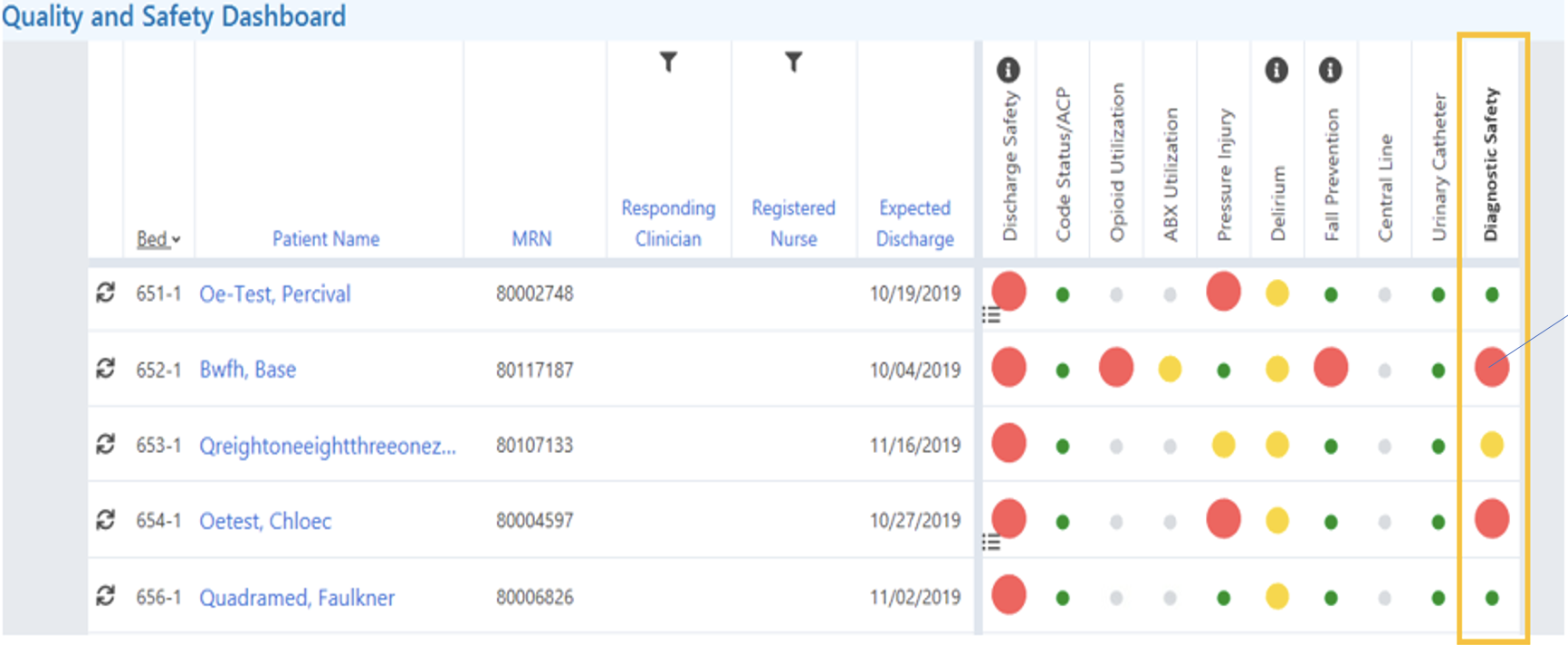

The Patient Safety Dashboard was designed to integrate with the institutional EHR to improve communication, usability, and patient outcomes by providing a unified view of critical data for healthcare providers.

Methods

The Patient Safety Dashboard was developed over 16 months, applying a participatory design approach to continuously collaborate with stakeholders (e.g., physicians, nurses, quality researchers) to refine the tool’s content, functionality, and integration.

The study followed a cluster-randomized, stepped-wedge trial design. Our clinician researchers systematically trained over 80% of unit-based nurses and engaged physicians through weekly meetings.

Feedback from providers was collected and used to refine the dashboard continuously. Clinicians also provided feedback on which healthcare data they would find most informative in the dashboard’s original 13 safety domains. Two additional domains were added later.

The dashboard used color-coded alerts to indicate patient risk levels and provided clinical decision support through visual flags and patient-specific views.

Dashboard usage was tracked automatically, and the Health Information Technology Usability Evaluation Scale (Health-ITUES) was administered to providers to assess usability. Research assistants observed provider use and collected qualitative data on the dashboard’s implementation. Data on dashboard use was analyzed descriptively, Health-ITUES responses were evaluated for mean scores and standard deviation, and qualitative feedback from research assistants was coded into major themes.

Results

The dashboard was used 70% of days the tool was available, with use varying by role, service, and time of day. Satisfaction with the tool was highest for Perceived Ease of Use, with attendings giving the highest rating (4.23). The overall lowest rating was for Quality of Work Life, with nurses rating the tool lowest (2.88).

Results of the intervention on processes of care was mixed, with some processes showing improvement after implementation while other processes showed no effect or a negative effect. On-treatment analyses with intensity of dashboard use was also mixed. The study provides many important lessons on how best to design and implement these types of tools.

MySafeCare

Patient preferences for automated and mobile reporting of safety concerns.

Background

Hospitalized patients and their care partners have valuable and unique perspectives of the medical care they receive. Direct and real-time patient reporting of safety concerns could provide opportunities to improve patient care.

Methods

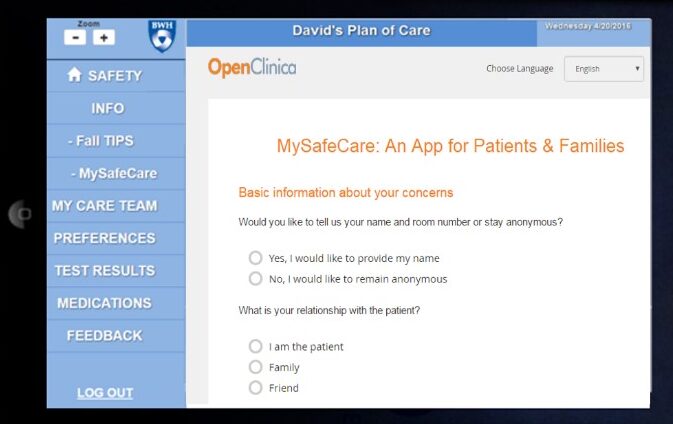

Utilizing a randomized stepped-wedge implementation approach, patients and care partners were enrolled daily using a study-provided tablet or their own device, with the portal accessible through an email login.

MySafeCare allowed patients and care partners to submit safety concerns across nine categories, including free-text narratives and options for anonymity or self-identification.

Submitted entries triggered automated emails to unit leadership and the research team, with submissions viewable on a secure clinical dashboard.

Usage of MySafeCare was analyzed, including submission rates per 1000 patient-days and optional demographic data. Submission characteristics, frequency of category selections, and portal visits were reported. Comparisons were made between pre- and post-intervention submission rates to Patient Family Relations (PFR). Thematic analysis of free-text concerns identified common themes and relevant patient safety risks.

Results

There were 46 submissions to MySafeCare, and 33% of concerns received were anonymous. The overall rate of submissions was 0.6 submissions per 1000 patient-days and was considerably lower than the rate of submissions to the PFR during the same period (4.1 per 1000 patient-days).

Identified themes of narrative concerns included unmet care needs and preferences, inadequate communication, and lack of trust.

Though the submission rate to the application was low, MySafeCare captured important content directly from hospitalized patients or their care partners. A web-based patient safety reporting tool for patients should be studied further to understand patient and care partner use and willingness to engage as well as potential effects on patient safety outcomes.